It is a little known fact that Cecil Rhodes planned to extend the railway that ran from Cape Town to Muizenberg with a branch line that would terminate at Hout Bay. Already an extension of the line to Sea Point had been considered, to link up with Camps Bay and Hout Bay, but Rhodes, as usual, had a hidden agenda. This was to establish a station at Groote Schuur for his personal convenience. His enthusiasm for the railways had been kindled by his experiences with the railway systems in Great Britain on the many occasions when he revisited the country of his birth, and particularly from his time as an undergraduate at Oxford University, for it was there that he had the time and acquaintances to experience the Railwaymania that was sweeping through the country; earning millions for speculators and landowners, and providing a living for a new type of skilled man who called himself “An Engineer”. This is the story of one such engineer, who, like many people, came under the spell of Cecil Rhodes. His name was Percy Ashenden.

It was in his college buttery that Percy first met CJ, as he came to call him, and, from this casual meeting, found himself, one day, standing at the rail on the Royal Mail steamer watching the bulk of Table Mountain materialising out of the sea fog, as it was dispersed by the warmth of the rising sun.

It was a similar morning on October 7th, 1875, in the City of Oxford, where, from his vantage point on the station down-platform, a railway employee leaning on the handles of his barrow could see the puffs of steam and smoke rising above the trees in the middle distance that obscured his view of the locomotive itself. There would be any number of young “undergrads” on 11.40 express from Paddington, calling at Slough, Maidenhead, Reading, Didcot and finally Oxford, because this was the last Friday before term started on Sunday. The porter couldn’t read or write, but he could tell the time and count his tips, and knew his way around all the colleges better than most of their permanent residents, the “Dons” as they were called, and certainly better than any of the commoners and scholars whose occupation of these hallowed cloisters was truncated into nine short eight-week terms.

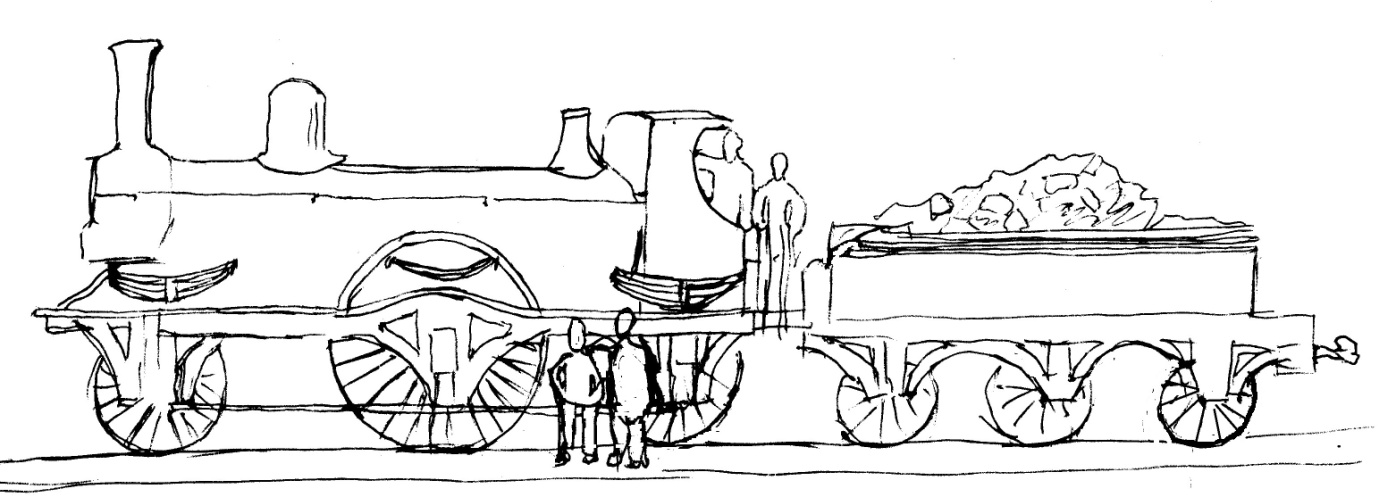

As the train pulled alongside the platform with a hiss of steam from its cylinders and the clunks of the passenger coaches running their buffers together, the doors were already half open and young men were leaping onto the platform before the train had come to a halt. For some of them, train travel was “old hat”, but for others it was the first time they had experienced the noise and smell of steam traction. For Percy it was neither. To this young man, rail travel was a religion and would, in due course, be his means of livelihood.

As was his wont, Percival walked to the front of the train to study the locomotive. It was a 2-2-2 Daniel Gooch design built at Swindon works some thirteen years earlier, but in wonderful condition with a full head of steam ready for its next run, in this case back to London an half hour later. A voice spoke from someone who had materialised just behind his right shoulder,

“Wonderful, isn’t it. Nearly 30 tons of steel with 130 pound boiler pressure and when the driver opens up his regulator” (which he obliging did just then) “the 7 foot driving wheel turns majestically and away she goes....” as the locomotive, now uncoupled from its coaches, proceeded noisily to the water tower and coal yard some 100 yards away for replenishment.

Percival swivelled round and found himself face to face with a tall man, a few years older than himself, with pale blue eyes, a sunburnt complexion and wearing a rather shabby corduroy suit.

“That’s the future for Africa” continued the stranger, when he could make himself heard again, ” A railway from Cape Town to Cairo.”

Changing the subject abruptly he went on, “You a Freshman?’

Percy was not sure if this was a question or a statement, but he answered yes, anyway.

“What college?”

“Oriel”

“By Jove, that’s my college. Well, well, let me walk up with you and help with your bags.”

The walk was a pleasant one, crossing the river, up through the parish of St Ebbs, down the High Street, turning right into Oriel street and Oriel Square, which was faced by the entrance to the college buildings.

The stranger kept up a continuous commentary about all manner of things that came to his mind as were triggered by the sights, with very little prompting from Percy.

Leaving Percival at the College gate, saying rather cryptically that he had to pay his landlady in the High a visit, and settle some accounts, the stranger suggested they meet again in the evening in the College Buttery and introduce themselves properly over a jar of Bass.

Oxford, at this time, was at its apogee. More than six hundred years of history had passed since Walter de Merton had founded his college in 1274 to take care of the carnal and spiritual needs of the students of the burgeoning University, an example that had been followed by other benefactors throughout the centuries, such as Edward II, Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII, Bishop Foxe, and others culminating in a collegiate system, by the time of Percival’s matriculation, of twenty colleges under Royal Charter.

Athletic sports, such as Rowing, Association Football, and Rugby Union Football were played by teams representing each college against other colleges, and collective teams already represented the University in trials against their counterparts at Cambridge. It was certainly an ambition of Percy’s, as well as gaining an honours degree, to participate in these games, and, if up to it, to gain his “Blue”.

Percy reported himself to the College Porter, a very important College servant (all full time employees were called servants), who proceeded to advise him on the rules and regulations that would affect his life as a member of the College and the University, and, more usefully, introduced him to his “Scout”, another college servant, who would effectively, or ineffectively (as was the case with some older servants), be his manservant during his tenure of rooms “in College”. Alf, for that was the name of his Scout, helped Percy with his bags across the quadrangle that spanned the space between the Porter’s Lodge on one side, and the ground floor “sets” and the staircases to the upper “sets” on the other three sides, and led him up one flight of stone steps to a landing from which a stout oak door on the right side opened onto a large sitting room furnished with two leather easy chairs, a chest high desk, a stool and a book case. Through a door in the far wall could be seen a second smaller room containing an iron bedstead, and a washstand equipped with a quart jug and enamelled basin. Both rooms had windows overlooking the quad, and the whole scene was one of light and air, if somewhat frugal. Alf, the Scout, showed Percy his own quarters, which was essentially a small kitchen on the landing between Percy’s set and the one opposite, from which he, Alf, could provide tea and muffins on demand, and spirits, wine and beers if ordered in good time from the Buttery, and any other comestibles provided from Percy’s purse for entertaining his visitors, or his guests at breakfast, lunch or dinner parties. Alf did not explain how Percy would be able to do all this, and keep up with his studies. That, as they say, is another story.........

The next few hours were taken up for Percy with unpacking and sorting out his clothing, stacking his books on the bookshelf and being constantly interrupted in these labours by fellow students barging into his rooms and introducing themselves and expressing the hope that Percy would join in the pastimes that were of their particular interest or bent. These ranged from Rugby Football, to Theatricals, to Choral Singing and Religions of various hues, and the Oxford Union which was the epicentre for Political Debate. None of them mentioned studying for their degree! So it was that, as the sun went down and the darkness drew in, Percy made his way to the college buttery, where the students would foregather to drink a pint or two of beer before entering the Dining hall for dinner. However, as Term officially only started on the following day, the meal was informal and most students would take the opportunity to eat out.

The stranger was already in the Buttery when Percy entered, and was sitting with some friends talking about life in Africa, which to Percy’s first impressions, seemed to be a preoccupation of his. The stranger caught sight of Percy and hailed him to come over and join his group, introducing him as “His Future Railway Engineer”, much to Percy’s embarrassment.

“Look here” said the stranger, having settled Percy next to him on the bench, “I shall now introduce myself formally to you. My name is Rhodes, Cecil John Rhodes, but my friends call me CJR or CJ for short. I’ve got a business in the Cape Colony, in Africa, which is why I talk so much about the place. And I’m here to get a degree, because who can call himself a man without a foundation in the Classics.”

“What sort of business is that?” asked Percy, after taking a sup from his tankard. “Diamonds!” replied the other.

The other men at the table raised their eyes heavenwards, as CJR proceeded to demonstrate his favourite party trick. Putting his hand in his trouser pocket, he pulled out a matchbox and slid its drawer open to reveal some rather unimpressive glassy pebbles. Holding one of them, the size of a broad bean, up to the flickering candelabra, Percy could see the way the yellow candlelight was intensified through the diamond into a brilliant white-ish blue. Percy was entranced. It was clear that this rather tall, lanky fellow was a man of some substance, despite his rank in the University hierarchy being just one rung above his own, that of a second-year man. He couldn’t think why CJ, as he was, by now, accustomed to call him, should take him under his wing, but there it was.

“I think”, said CJ, after downing a second tankard of beer, “it’s time we went for dinner, or the best cuts will have been taken. Are you coming along, Old Chap?” he asked Percy.

“I don’t know...............” replied Percival, “I’m not sure that I have enough cash with me, and I cannot get to the bank until Monday”

“Nonsense,” replied the other, “To start off with, you, not being a member, do not have an account with Vincent’s so I shall pay for your rations, and even if you could pay, I would take it badly if you insisted. Let’s be off.”

Coming out into the night air from the confines of the Buttery was a blessed relief for Percy, what with the tobacco smoke emanating from numerous pipes and even a couple of cigars that declared their smokers to be more lavishly endowed than most students. Already dark with a touch of early frost in the air, the two pals made their way out of the college gate and turned up King Edwards Street and into the High. Here they found the shop of Vincent & Co, printers and stationers to the University, and there, in the two floors above the shop-front and accessible by a staircase from a small door set in the wall beside the shop entrance (now closed and locked up for the weekend) warm candlelight spilled out of the un-curtained windows behind which passed from time to time serving girls carrying pots of beer and plates of meat dishes.

Taking the stairs two at a time, Rhodes was on the first floor landing before Percy had time to blink, and following his rapidly disappearing back through the open doorway off the landing, found himself among a crowd of very jolly, loudly conversing young men of all description, but clearly united by their love of their own voices and opinions.

One in particular stood out, mainly because of his height and his bulk. Rhodes was by no means a short person, but he was dwarfed by the man who disengaged himself from his companions and strode across the room with his hand outstretched to clasp Rhodes by the elbows and steer him towards the serving hatch in the corner of the room. “My Dear Fellow, how very good to see you again. You must bring me up to date with all things African. Are you still peddling diamonds? How are you getting on with Marcus Aurelius?”

“Oscar,” interjected Rhodes when his companion paused for breath, “ I want you to meet a young friend of mine” he said, “ This is Mister Percival Ashenden and he’s going to build me a railway from Cape to Cairo”, he said pulling the Freshman into the conversation.

“Mister Ashenden, this is Mister Oscar Wilde, a classics scholar from Magdalen, who has the goodness from time to time of helping me translate some of the more difficult texts my Tutors give me.”

“Oscar, I know this will come as a bit of a shock to you, but Percy here intends to try out for the University Rugby team.” Turning to Percy, Rhodes added, “Oscar detests physical sports and considers himself something of an aesthete and a poet, but a more affable chap you couldn’t hope to meet.”

At some point in the succeeding conversation, mostly dominated by Oscar with his witticisms and bon mots, when Oscar was distracted by another acquaintance, Percy asked Rhodes what he meant by him, Percy, trying out for the University Rugby Team?

“Oh!”, said Rhodes, “I saw you had a pair of football boots in your dunnage and you look a fast runner so I thought, ‘Why not?’ and while you were spending your afternoon coming to terms with your accommodation, I gave your name to this year’s president of the University Rugby Club as a candidate for one of the wing positions in the annual challenge match against Cambridge. They want to try you out on Monday afternoon when they have a game arranged against a team drawn from the Oxford Townsmen!”

The rest of that evening passed in a blur of beer, whisky and witticisms from Wilde, Rhodes, and their fellow members of Vincents, and by the time he was due to re-enter the gates of Oriel at the hour of nine p.m., as signalled by the chimes of Big Tom, the Christ Church Bell, he was not too steady on his feet. Rhodes, who had digs in the High Street as opposed to rooms in the College, saw Percy safely to bed, and was let out by the porter who was always willing to bend the rules for Mister Rhodes.

The next day, being a Sunday, Percy had time to recover from the effects of the night before without too much pressure, and spent an otherwise pleasant hour or two in the college chapel before joining the other freshmen and resident undergraduates for lunch in the College Hall. Sitting amongst his peers, Percy and his neighbours at the refractory table exchanged their personal histories and their opinions on their surroundings and their experiences of Oxford Life so far, and the normality of their chatter made the memory of the previous evening’s events seem to Percy part of a dream.

The following morning Percy met his Tutor for the first time, a man who looked rather young to be an Oxford Don, and indeed as one of the modern breed of mathematicians so he was. Until this time, the scope of the mathematics taught at the University was Euclidian Geometry (in the original Greek) and algebraic logic. However, the development of Newton’s calculus (in Latin) and the Victorian industrialisation with its stimulus to engineering concepts had given rise to a new breed of Dons whose attitude to the accumulation of knowledge was directed towards usefulness rather than for its own sake.

After making some cordial remarks by way of a greeting, his Tutor, whose name was Samuel Jowett, said, “You will need to make Responsions as soon as possible so I can assess your Latin and Greek understanding. However, judging by your report from your old Headmaster, they shouldn’t be a problem. You will, of course, attend lectures on Mathematics, and I will go through the material at our weekly tutorial. I hear you have already made the acquaintance with our Mister Rhodes. My advice is, don’t get too drawn into his circle. He’s here to get an Oxford degree so he can show off back in the mining camps of South Africa, but his commitment to learning for its own sake is questionable.”

“Thank you, Sir”, responded Percy. “I fear I am already committed rather more than you would wish. I am to play in a Rugby match this afternoon against a team from the Town at Rhodes’ instigation. Should I scratch my name?”

“Good God, No”, replied Samuel Jowett, “Mens sana in corpore sano! Besides which, Oriel is in need of a Rugby Blue. I suppose you’ll play on the wing, being a bit sparse for a forward? My advice? Keep out of the melee as much as you can, and run like hell when you get your hands on the ball”

With these words ringing in his ears, Percy took his leave from his Tutor, and went off in search of a light lunch before his sporting appointment at the University Parks.

The University Parks, where a playing area had been marked out by flags on four-foot ash poles on each corner 100 yards apart, with extra flags marking the positions twenty-five yards from each goal line and half-way between the goal lines, and goals erected in the familiar H shape on each goal line, was about a mile to the North of where Percy’s college, Oriel, was built. Having changed into his sport’s “bags” in his rooms, and slinging his football boots over one shoulder, Percy crossed the High Street as one o’clock was tolled by St Mary’s Church clock tower, and he made his way across the Radcliffe Square, past the Sheldonian Theatre and along the Northbound Road leading to the Parks. As he walked, he was joined by an increasing number of young undergraduates, keen to inspect the talent available for taking on the “Tabs” (short for Cambridgendians), their arch rivals, later in the term. Long before he reached the playing area, Percy could feel the rats gnawing at his stomach at the prospect of his forthcoming trial.

On his arrival at the playing area, he was greeted by the Captain of the University side, whom he recognised from his dinner with Rhodes at Vincents the previous Saturday, and given a dark blue jersey and dark blue stockings to wear for the match. With the Captain were several other players, and the rest of the “Fifteen” selected for this match arrived within minutes of Percy. There was a noticeable increase in the tension in Percy’s stomach as he and his team mates pulled on their boots, and the Captain started to lay down just how he wanted the game played if they were to beat this opposition from the Town Club. Most of the team were a couple of years older, and therefore more muscularly developed, than Percy, and were obviously less overawed by the sight of their opposition, when the “Townies” arrived in a Charabanc ten minutes later.

The two captains met and conferred over the time for play, the appointment of a time-keeper (who would also adjudicate any dispute over an infringement of the rules) and the ethics to be respected, such as no punching with fists, no gratuitous kicking of opponents and so on. To Percy, as he waited in his allotted position on the field of play for the game to start, his opponents looked enormous in jerseys that were distinguished by their alternate hoops of Green and Yellow, carried over into their stockings, and their white “bags”. In contrast, Percy and his team-mates wore their dark blue jerseys, grey “bags” and dark blue stockings. The oval ball was placed on the centre spot of the field, and the two teams faced each other ten yards either side from where the ball stood on its end. The time-keeper consulted his watch, raised a whistle to his lips, and gave the blast that would be the signal for both teams to rush pell-mell to retrieve the ball and thrust for the opposition’s goal-line.

For some five minutes after the time-keeper’s signal to start the match, nothing much seemed to happen, as the ball was buried under the mass of bodies comprising the forward players of both sides. There was some rooting for the ball with their feet, and much pushing and shoving by each team in an effort to move the scrum, and the ball with it, towards the opponent’s goal line. Quite suddenly the ball appeared from the melee of legs and backsides of the Blues team’s forwards, and the scrum-half snatched it up in his hands and in one continuous movement sent the ball flying towards the back-line player standing behind and to his right. At the sight of the ball emerging from the scrum and the alacrity with which the scrum-half moved the ball away from the opposing forwards, Percy’s nervousness evaporated and he started to run in echelon formation with the other back-line players towards their opponent’s goal line. Quickly, and without a break in his stride, each man caught and passed the ball to the next, so that the movement of the ball appeared to accelerate towards the corner of the playing area being defended by the “Townies”. In his allotted position of winger, Percy found himself having to raise his speed of running to a sprint, so that when it was his turn to receive the ball from his centre he was going flat out towards the corner flag. His opposite number was caught flat-footed by the speed with which the Blues players got the ball into the hands of their winger, and Percy easily evaded his opponent. Nevertheless, a “try’ would only be given when Percy, or one of his team, crossed the goal line and grounded the ball, and the Townies’ full back stood squarely between Percy and the goal line. He was a big man, and nicely balanced on his feet to move either way to cut Percy off in his run for the line. Although Percy had outrun many of his schoolboy opponents by going outside their space, he instinctively knew that this looming giant of a man would drive him crashing over the sideline with the full force of his body weight and momentum behind his shoulders. He swerved in field and this meant that when his path and that of the full back crossed, at least there was little or no momentum behind the full back’s tackle. These thoughts, of course, were not really all worked out to their logical conclusion in the split second that Percy implemented his decision, but that was immaterial. The result was that, not only did Percy avoid a bone crushing despatch to oblivion, but his inevitable prostration on the ground brought about by the full back’s tackle was slow and relatively gentle. So much so that, the Captain of the Blues, racing to catch up with Percy, was ideally situated to receive a despairing pass that Percy made as he fell to the ground, and, there being no other opponent between himself and the goal line, the Captain dived over to score the try. Picking himself up off the ground, Percy felt his chest bursting with pride. He had made the try possible, and had given the glory to his captain. He only then saw Rhodes and Wilde, two tall men, each as big as the full back he had flat-footed, shaking each other by the hand as if it were they who had made the try possible! And, in a way, it was.

The rest of the match took its course, with Percy making some fine runs and several saving tackles on his opposite number. With the gloaming twilight, and the mist starting to rise from the ground and mingle with the steam emanating from the sweaty bodies of the players, the timekeeper signalled the end of the playing time, and the two captains conferred over the score sheet. The result was declared in favour of the Blues, and a tired, muddy and happy Percy traipsed off the field to return to his rooms in Oriel, in the company of a number of other football enthusiasts, and enjoy a steaming hot bath. Once he was clean, dry and dressed, Percy made his way once again to Vincents, where jugs of beer awaited the conquerors and the conquered alike. And so a most convivial evening ensued; and this time Percy took care to keep his intake of beer within the bounds of proprietary, and thus avoid a repeat of his hangover experience.

During the course of the evening, Percy was taken to one side by the Captain of his team who asked him to go into serious training with the team with a view to playing in the match to be arranged with their counterparts at Cambridge University. Percy told Rhodes the following morning when they met up for a mid-morning coffee, before getting down to some academic work (Percy was finding it increasingly hard to find the time to catch up with his studies). Rhodes was suitably impressed and said that if, in due course, Percy and his team could beat Cambridge, he, Cecil John Rhodes, would stand the whole team to dinner and a show in Town (by which he meant London’s Theatre district). This, as Percy was to learn, was a typical Rhodes gesture and his way of expressing his pleasure in someone else’s good fortune.

And so the days of Percy’s first term at Oxford passed, more quickly than Percy would have liked. Usually a late breakfast in hall would be followed by a few hours studying, interspersed with the occasional lecture, and after a sandwich for his lunch he would join the other members of the rugby team for some practice and fitness training, or for a game against one of the London Rugby clubs to prepare for the “Blues” match against Cambridge. Each week he would meet with his tutor for an hour or two, during which time the tutor would assess his progress, give some direction for his studies, and quiz him about the rugby team’s chances! The weather turned from the benign soft Autumn days to the damp, overcast, heavy, shortening winter days as the end of term approached. The big match was to take place in the second week of December on a neutral ground in London, in the village of Twickenham, where the Harlequins Rugby Football Club had offered their facilities. Most of the undergraduate members of the two universities made their way to London for the occasion, staying with friends and family, and friends of the family, to be present in the stands and on the touch-line to cheer on their team on the Great Day.

Percy was the only freshman in either team, the other players all being somewhat older and experienced in the adult game. When he arrived at the ground as instructed at one o’clock pm, he was overawed to see such a mass of people already milling around, some with tankards of beer already in their hands, with their multi-coloured scarves announcing their colleges, or plain blue scarves for those who had previously represented their University at one of the manly sports – Association Football, Rugby Football, Rowing, Boxing, and Athletics. Percy made his way through the throng, with some who recognised him wishing him well, and entered the pavilion where the teams would change into their playing gear and do their warm-up exercises. This was the moment when Percy came face to face with his opposite number, a man who had played for Scotland in the match against England for the Calcutta Cup. Percy was fully conversant with this man’s attributes, having read the newspaper reports of the matches he had played in, and meeting him in the flesh and appreciating that they would be facing off in a gladiatorial contest as equals (at least, until events proved otherwise, thought Percy) gave him a frisson of pleasure. The two teams were allotted separate rooms in which to make their preparations, each equipped with a communal bath for taking the mud off their bodies after the match, as would be inevitable on a damp December afternoon in London, even in the case of a wing three-quarter.

Placing his clothes on the back of a chair provided, Percy slowly undressed down to his underwear and pulled on a pair of grey knickerbockers, some blue woollen socks to his knees, and pulled the dark-blue serge jersey of his team’s colours over his head, covering his torso. Sitting on the chair he placed his feet into a pair of leather boots specially made to fit him by an Oxford shoemaker, and to be light but firm on his feet, and equipped with studs on the soles and heels to assist purchase on the muddy ground. At this stage of the afternoon, his boots were shiny black after he had spent the evening before bringing out the gloss of the leather. As he laced them up, he reflected that they were unlikely to remain in this pristine state once the match got under way. The smell of liniment, liberally applied by some members of the team to their muscles and joints now pervaded the changing space, and the air in the room grew warm and thick with the heat of their bodies as they made their stretching exercises.

The referee who would oversee the conduct of the game put his head round the door and asked the captain to join him and his opposing number for the toss of the coin to decide which team would have the privilege of choosing the end to defend, and who should have first touch of the ball (the Kick-off). The captain returned, having, apparently, won the toss and announced that Oxford would defend the pavilion end (there being a strong breeze from that end which would assist any first half kicks at goal) and the opposition would kick-off, giving his team the first chance to handle the ball.

Now came the time to run out onto the pitch (as the playing field was called). The Cambridge side had already run on, being the winners of the previous year’s contest, and the roar of support sent another frisson down Percy’s spine. Now it was their turn, and as they ran through the phalanx of supporters (from both universities) that lined the path from the pavilion steps to the edge of the pitch Percy was almost deafened by the roar of the crowd. There must have been almost five thousand. The nervousness that had been building up inside Percy’s vitals from the moment he woke up that morning reached a crescendo. He felt that a swarm of bees were zooming around in his stomach. “If I’m not sick,” he thought, “It’ll be a miracle”. No, he wasn’t sick. And the miracle occurred at the first blast of the referees whistle. All signs of nervousness disappeared as Percy sprinted towards where the ball was going to drop after the Cambridge captain had taken the opening kick of the match. It was towards his side of the field, and well over the heads of the scrummagers. Catching it cleanly as he ran back towards his own end, he turned to face the oncoming rush of the Cambridge forwards as they bore down on him. If he wasn’t to be buried under eight light-blue bodies, Percy had to think and act fast. He did the only thing he knew how. He ran. He ran away from the safety of the touchline towards the middle of the pitch, and in doing so completely wrong-footed the Cambridge scrummagers who fully expected him to either run into touch or remain frozen to spot to take whatever punishment they cared to dish out. As it was, by the time they realised which way he was going, he had already rounded their left flank and was running down the middle of the pitch with only the Cambridge back-line between him and the try-line. Of course, his running free could not last, and he was brought down to earth literally, with a thump, when the Cambridge scrum-half, covering across the field, made a diving tackle taken straight from the text books, yet to be written.

As an opening gambit, Percy’s first run set the tone of the game. Both teams were intent on running with the ball in their hands, eschewing for much of the time the kick and chase tactics so often used by representative sides playing each other and the result was an exciting, high scoring contest with plenty of daring runs and thumping tackles.

With Cambridge leading by 21 points to 20 and two minutes of time left, Rhodes had decided, sadly, that he would need to cancel the reservation he had made for sixteen persons at the Savoy Grill. But he had reckoned without our Percy. The contest had taken its toll on both teams. The Cambridge captain had suffered a broken arm and had had to retire to the sidelines, from where despite the pain of his arm, he encouraged his troops. Two of the Oxford team were hors de combat , one being knocked unconscious, although recovered enough to run aimlessly around the pitch, and the other with a severe cut over his eye preventing him from seeing clearly through the flow of blood. Percy, caked in mud, was, however, otherwise fighting fit. Now, he realised, more than ever, was the time to keep the ball close to the chest, and run like billy-oh. Picking up the ball in his own 25 yard line from the feet of a spirited if slow dribbling surge from the Cambridge forwards, he ran back towards his own goal line swerving first left then right, but still moving backwards. The chasing forwards were like mice mesmerised by a snake, not knowing which way to move to catch him. Somehow, by telepathy, they agreed to split their forces, and half of them moved right and the other half moved left, to cut Percy off. Meanwhile, the Cambridge backs had spread across the field to counter any sort of back-line movement the Oxford backs might attempt. Percy saw his chance. Spinning around as if to kick for touch, as the two echelons of Cambridge forward threatened to engulf him, he darted forward between them leaving their flailing arms grasping fresh air and broke through into open space. It was now a race for the line. On his left was the Scottish International winger, starting to move sideways towards him. From the right the rest of the back line were turning on their heels and making to cut him off at the corner, and in front of him was 100 yards of clear ground. Almost eighty minutes of muddy toil had taken its toll, but then the adrenilin kicked in and Percy flew. He had got past the outstretched arms of the Scottish International Winger, who might had stopped him if he had made a dive for his ankles, and was now consigned to try to catch Percy from behind. There are any number of schoolboy opponents who would testify to the impossibility of doing that, even for a Scottish International winger! The covering backline did their best but one by one were outpaced by Percy, except for one very fast-running centre. He would have brought Percy down a couple of yards short of the goal line, but as he dived for the tackle, so did Percy, for the line. Of course, it seemd like a despairing effort on Percy’s part, being six yards short on his last step. But three yards through the air plus two yards sliding on the mud brought Percy’s chest where he was hugging the ball over the line and into the score-book. Three points for a try, and Oxford were declared the winners by 24 points to 22.

Rhodes was, of course, as good as his word and that evening the team had a raucus evening at the Savoy Theatre where they were entertained by an operetta called Trial by Jury written by W.S Gilbert with music by Arthur Sullivan that was enjoying unprecedented popularity, followed by the sort of slap-up meal only a London restaurant can produce.

Percy was asking Rhodes, as they swirled their post-prandial brandies around the glass, what he was doing for Christmas.

“Oh”, replied Rhodes, “I have an aunt in Norfolk who I can stay with. I’d have liked to return to Africa, but if I want to get my degree, I can’t afford to miss any dinners in Hall next term, and I couldn’t guarantee to get to Cape Town and back in the six weeks between now and the start of the Hilary Term.”

“What about coming to Yorkshire?’ suggested Percy, “You’d be welcome at our place and there’s plenty of room. Father would be tickled pink to see you, as I’ve been writing to him about the people I’ve met down here, like Oscar, you and the other blades, and I know you can ride and you’ll enjoy a hunt or two.”

Percy waited expectantly. Rhodes looked around at the rest of the dinner party and weighed up the bonhomie he saw there against his aunt’s rather quiet existence. He turned back to Percy.

“I’ll arrive at your local railway station on the 24th”, he said decisively. “Just write the name down here” he continued, pulling out a pocket diary, “and your address, and I’ll telegraph you with my time of arrival in due course.”

To Rhodes, it was as simple as that. No asking directions, no irrelevant questions. A decision made and a decision acted upon. Already, Percy had known Rhodes long enough, that if he said he’d do something, he did it.